Storhogna-Fettjeåfallet: Notes on walking

A photoliterary essay that experiments with an alternative form of academic writing and elaborates on walking as embodied experience.

Amidst a sprawling (seasonal) community, Emmelie and I started our 13-kilometre mountain-hike. A few hundred metres above sea-level, the houses were folded into the mountain landscape amidst berry bushes and miniature birches. Polyommatini butterflies set their wings in motion in the low-shrubbery terrain or hid when we passed by. Rain had fallen briskly over the past few days. The night before, it had clattered on the roof and could be heard running down the drainpipes outside. And with the rain, the paths had turned to mud. Many had become slow and steady streams, finding their way on the pre-made pathways. Walking them sometimes meant sinking down into unknown worlds. We followed the initial stretch for a kilometre or so before turning northward to ascend the mountain-top Högtelen.

There is a grace to walking. By walking, we feel the surfaces of places and landscapes beneath our feet. We multisensorially apprehend places and landscapes we move through by mediums different from the static-but-mobile observer of a car or railway passenger. How places and landscapes offer means of ‘affect’ to the body moving through them has become of growing interest in the realm of geographic and anthropological research and methodology as of late. Emphasis has been placed on the forms of knowledge and ways of knowing that are engendered by how we move through/with/in places and landscapes. By walking, this literature often suggests, we connect to places and landscapes, apprehend them, and feel them through our different cultural embodiments. In other words, by walking we forge a particular way of knowing a place unlike other forms of knowing it, sometimes implying distance and sometimes closeness.

As we approached the top of Högtelen, the shrubbery cleared and a view began to hint in the distance. The poles often placed into the ground to guide people across mountains within Sweden’s territory pointed the way for us. Sometimes rocks had been painted to give indication of the way forward, and at steady intervals signs showed us where to walk if we wanted to get to Storhogna or Vemdalen, to name two. Yet, there was an ambiguity to the paths. At certain locations, it split up without an indication on the map. A wrong turn unguided by a compass could quickly set us out on a path non-intended—albeit full of potential in itself. Sometimes unsure if the path was a stream or the path itself, we continued in a dubious attempt at navigating a landscape both marked and unmarked.

We are often guided in our walking. When walking a designated path this seems to stem from the body becoming automated by movement itself, with one movement necessitating the next and granting a sense of progression. Though while spurred by the repetitive movement of a body in motion, landscape representations point us into motion too. Signs tell us how far we have gone, how far we have left, and where we are in a planned and mapped-out system of paths. Signage points bodies in the ‘right’ direction, colours painted on surfaces hint the ‘right’ path forward, kilometre-indications grant feelings of reassuring accomplishment. Being guided to move on a designated path and signage to someplace in particular, the body traverses distances largely without thinking what distances it has traversed.

However, the potential to break is always there. To step outside treaded paths is to allow for something else. Like when picking mushrooms, the path becomes obsolete and the movement becomes from one fragmentary sight to another through sometimes difficult-to-navigate terrains. In this mode of walking, we cut through, avoid repetition, carve a new path. So, while walking can be characterised by going someplace in particular—guided on our way—the potential of intentionally or unintentionally breaking from the mundane can suddenly come into being. The two impulses merge and diverge in varying intensities (see Stewart 2007).

A valley opened up before us. Clouds covered the sky with light and dark patches intermingling. Lone trees and patches of shrubbery were like cut-off islands. The bogland before us sometimes felt more like an overgrown lake than a valley. Afar we could see Bräckvallen, the conglomeration of small cabins toward which we headed. A path seemed to lead directly to them. Slowly, the gathering of houses grew nearer, but only slowly. The wind had free reign through the valley.

Walking is imbued with feelings of accomplishment. Of the body having moved by its own energy through (in)accessible terrain. To have sustained itself in what through today’s discursive analogies could be referred to a machine or a computer consuming energy drawn from a charged lithium battery pack, fed into the engine when needed. Though while walking can be graceful as something that connects us to places, the rosy romanticism of the walker with their walking stick oftentimes exists solely in hindsight. Walking means crackling joints, back-pain, feet sliding in the wrong places, wet feet, sweaty feet, blistered feet, cold-wet garments pressed between the backpack and the skin of the back. These things fade in the post-event representations. What we are left with are the sights seen, the sounds wondered over, the numerical stretch moved across.

We sat down and rested around halfway through the valley. Behind some shrubbery we found a refuge from the cold wind crossing the bogland. Some ants crawled around us. Besides the ants, all we saw were a few birds and traces of other animals having already left when we came. A few hundred metres away, two people roamed the bogland in search for cloudberries.

Walking implies encounter, but encounters have different dispositions. Feet against the ground, hands holding branches for support, the feeling of a mediated tactility through the walking stick. Bodies walking next to each other, crossing wet patches together, holding hands, brushing against one another. The risk of (unwanted) encounters with bears or elks looming as a potential to awaken both dread and curiosity. Encounters between walkers occur. Fleeting glimpses of ‘what are they doing?’, a brief ‘hello’ or a tired smile when crossing paths, a ‘heads-up’ of something to come to prepare the walking body. Walking implies encounter in the form of conversation. The movement of legs seem to set thoughts and voices into motion. Stories are awoken from the associations of a landscape passed through, sometimes diverging, sometimes linking, finding accordance in the landscape or discordance in place as the far-away and the present-close compete for attention.

Crossing the bogland, we skipped between patches to avoid the water luring in what first appeared to be solid surfaces. Until halfway through the valley, planks were solid and looked brand new, placed to enable a steady pace across the otherwise ill-fated terrain. The new planks only reached so far though, and for the rest of the crossing, they appeared as debris from sunken ships in the moss. Water cascaded on them, they were covered in water or could be seen through the water’s murky surface. But the cabins of Bräckvallen that we had seen in the distance were not far off now.

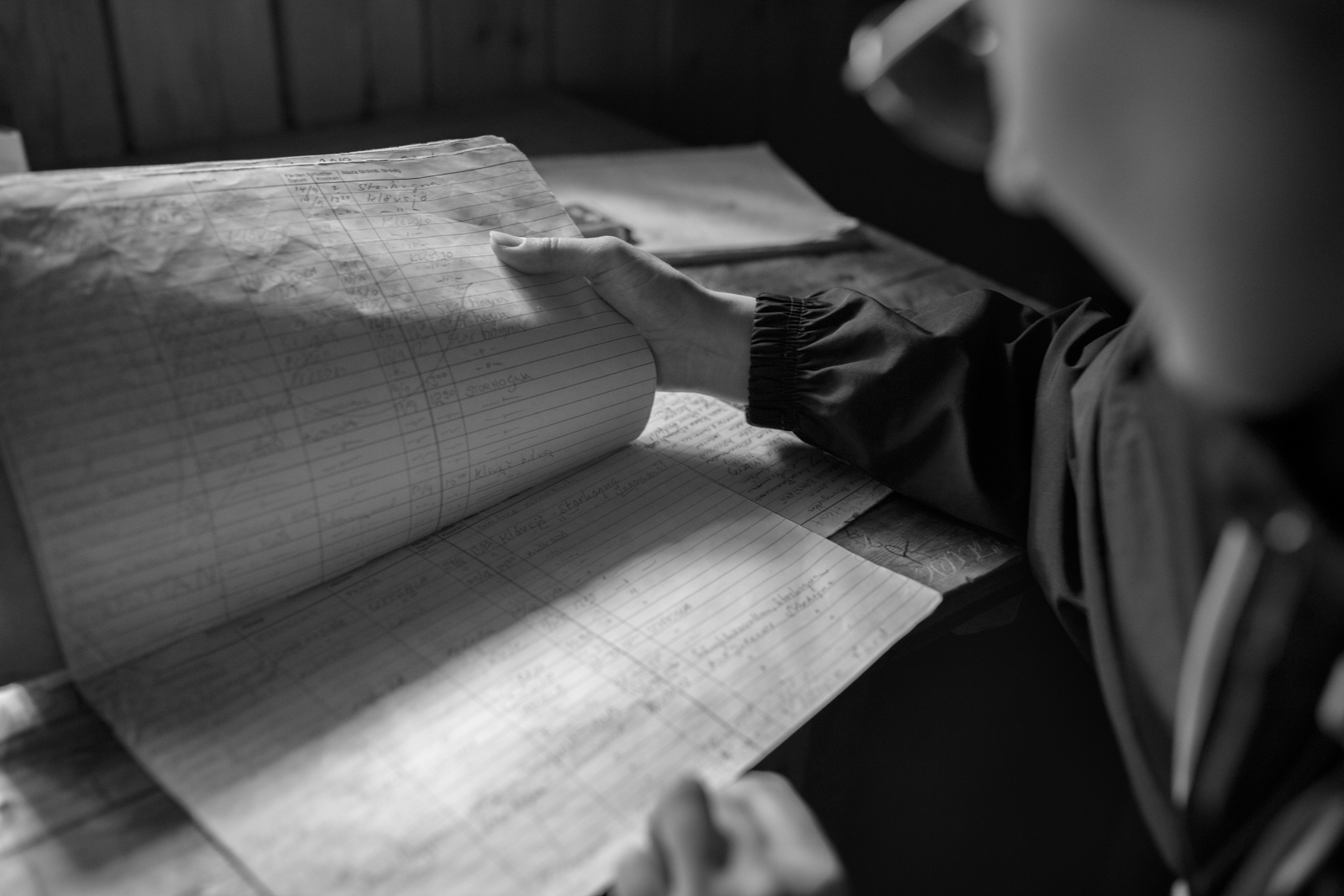

In a resting cabin around halfway through our hike and just a few hundred metres from the Bräckvallen cabins, Emmelie finds a book in which other walkers who have passed by have noted where they have walked from and where they are walking to. The list reaches back to the 80s. Together with names carved into the wooden walls, these indications of past presences give faint, ghostly insights into who has been here. It says something about who has opened the cabin door, who has closed it behind them, whose dripping sweat and its concomitant salts have become part of the wooden floorboards, whose breadcrumbs or skin cells lie folded into this place of past being (Edensor 2005).

When walking, we pass in the footsteps of others, both literally and figuratively. But not all places nor people have their past presences written into place. Many, have riffled through books like the one described above, read a few names, and then moved on. Walking, these leave their footsteps as traces in the mud which are then washed over by rain. The traces of past walkers might linger for a while, like the traces of animals having roamed too, but fade as wind, erosion, and rain morph the landscape into constantly changing but eerily durable forms.

We reached Bräckvallen. Without lingering though, we walked on. The streams on the paths were more intense now. On a slope running down to a small river, ants had been cut off from each other. They huddled together in groups on small islands as they tried to cross to the other side. The terrain became a hilly forest, with blueberry bushes, pines, birches, and mosquitos around. We neared the topside of the waterfall Fettjeåfallet. Coming up to the hillside of it, we walked as close as we dared before coming back to the main path. The way down was steep. Our feet were soar, and the before automatic movement had a growing notion of fatigue to it.

There is an endurance and a growth to walking. Feet grow stronger, legs are tired out but muscle spawns from lingering aches. It is a growth that does not solely exist as fragments of experience having left embodied and cognitive marks on us, but the walking itself leaves traces that move beyond experience and are part of the body’s future embodiments and movements.

The final stretch soon came into view. Growing tired, we zigzagged between other walkers as we headed toward the waterfall that we before had looked out over from the top of the cliff. The roar of it increased as we neared. The path went along a stream heading the other way, forging a longing for the feeling of water against skin. Parts of the path had been made into staircase-like structures, made slippery by water splashed up from the stream. Bridges were laid out to allow for easy passage. As the roaring waterfall came into view, we climbed over the last few rocks and sat down some distance away.

Beginning is often the hardest. To start walking, the first kilometre or two. Feet feel swollen, ache, legs are stiff, the walk feels daunting. Once these first steps have been completed though, the path ahead grows less cumbersome. Each step follows the next, each rock is followed by another, the landscape around appears to float by as parallax gives the illusion of hasty movement amidst a more-or-less stilled scenery. There is a continuity. A rhythm that once incarnated keeps the body moving. When that rhythm ends and the destination has been reached, the ache comes back, like a phantom drift to either keep moving or lay down and rest. Through walking we can traverse sights which the railway traveller only sees flicker by. If the car driver hastily sees a site pass wondering how it would be to loom here, the walker does the looming, stops, and tries to perceive the place as lived, even though new walking, new steps, soon follow. Along the way, walking leaves traces in thoughts, embodiments, sensory faculties, muscles, landscapes, encounters, and people. Guided and unguided, we walk.

This photoliterary essay has been an experiment with an alternative form of writing theoretically. For it, I have drawn inspiration from my recent reading of Kathleen Stewart’s book Ordinary Affects (2007) in conjunction with Elliott and Culhane’s edited collection A Different Kind of Ethnography (2017). Drawing insights from both and working with the theoretical backbone of ‘affect’ as used by Stewart (2007), I have tried to explore some recent interests in walking methodologies (e.g., Ways of Walking (2008) edited by Tim Ingold and Jo Lee Vergunst) through a hike Emmelie and I undertook a few weeks ago in Jämtland/Härjedalen (Sweden).

Though, while drawing on the combination of these texts, my main inspiration is perhaps Kathleen Stewart’s book Ordinary Affects (2007) and the way she experiments with a form of affective writing. In her book, she brings together social theory, speculation, lived experiences, and observations, as she fleetingly ‘captures’ a USA as a conglomeration of embodied affects. In so doing, she illustrates a theoretical way to perceive the world through (ordinary) ‘affects’. It is a reading I highly recommend for Stewart’s ability to both hint and explicate the relevance of social theory, and to do this in a language which breaks away with some of the more traditional style of academic writing without loosing its critical edge.

I have kept citations to a minimum for ease of reading, but for the interested one, here is a list of some of the sources that have been at the back of my mind during writing and which I can recommend for further reading:

Find this interesting? Consider supporting Viktor Aronsson by signing up for the newsletter.

When signing up you agree to your email being stored for the purpose of the newsletter. To have your email removed, click 'Unsubscribe' in the emails you receive or contact us directly.

RECOMMENDED POSTS